Let’s face it, coming from a catamaran world makes it difficult to imagine a long range sailing life in a monohull. It’s a mix of habit of course, comfort as well, and safety in any kind of rough sea condition we encounter. The layout makes you feel protected from foul weather, and we’ve been sailing her in winter without any afterthoughts. But for this project, we need to lay down everything on the table, especially when you see side by side the Exploration 52 and the Explocat 52, two equally appealing units from Garcia Yacht.

Safety wise, we’ve had our deal of strong wind, but never above F9, and we avoided most of the bad seas which occurred over our decade in the Med. We have experienced a few tricky situations when the larger size and obvious higher windage weren’t an advantage including while mooring in cramped places. But in our 24.000+ sailing journey up to now, we only reefed #3 once, on a sporty passage of the Bonifacio straight. So basically, we have no actual experience of the handling of a catamaran in very harsh conditions, combining heavy wind and large waves.

Of course, life on board is another matter, and we wouldn’t make many changes in this area for a future boat.

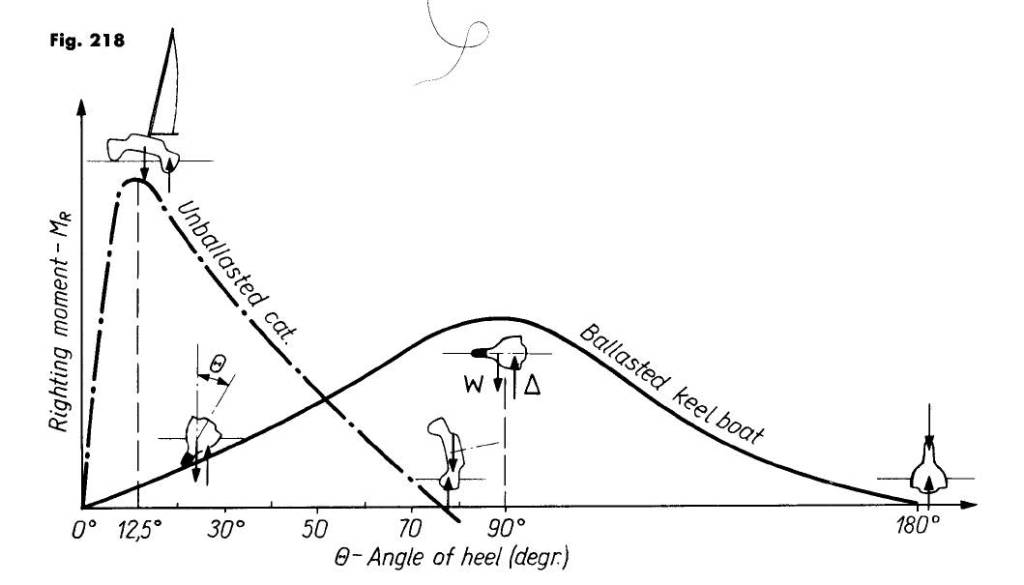

For such an adventurous sailing program, most conventional answers will say monohull is the only way to go. At some point in the conversation, the boat Godwin point, e.g. capsizing and righting moment, will come up, clearly not in favor of the catamaran.

You can cruise them up North if you avoid ice … a dicey proposition

Anonymous sailor about catamarans in an high latitude-related post (2015)

The monohull vs. catamaran debate has been raging for a long time. Back at the pub, after a nice day at sea, that’s surely a way to spark a no limit and passionate conversation, of equivalent magnitude to those of the Valladolid debate, or the legalization of marijuana. It is usually closed with personal choices and targeted sailing areas, on top of a definitive nod, and maybe a drink refill to cool things down. These are the most classic arguments we collected along the way:

| Monohull | Catamaran | |

| Speed | Higher wetted surface, especially while these recent large hull designs are heeled, will reportedly provide monohulls with a speed handicap. Well, it might depend on many other factors, such as sea states (monohull are more stable in crossed seas), hull design, weight distribution, … all the classics in fact. | Usually faster than “same size” monohull, credited with half the wind speed potential on average, though this will still depend on their key ratios (sail sqm/t) and weight distribution. Let’s take the Lagoon 55 and the Outremer 55 for instance, both GRP, both designed by famous VDLP architects. While the 1rt will measure 6.5 upwind sail sqm/t, the 2nd will be at a staggering 12.4 sqm/t, adding dagger boards to its speed-oriented design. |

| Upwind capabilities | That’s an endless controversy within the global one. Monohull will indeed upwind better than most recent “condomaran”, especially if equipped with this deep keel every sailor needs while sailing, and regret having while trying to anchor in this little secluded little cala. | Most catamaran have a long shallow keel, limiting their upwind capabilities. However, some brands include dagger boards (Catana, Outremer, Balance) for this purpose. And of course at the end of the day, taking into account the VMG and not the speed over water, this is a limitless harbor pub conversation. |

| Safety | In the most extreme situations, it all comes to “stability curve” and “righting moment”, although that won’t be the most attractive feature one looks at when considering a new boat. From this standpoint, obviously monohull have the advantage there. But in these extreme situations, any small boat design and their crew is at risk. Capsizing a monohull is likely to bring her down, while catamarans are supposes to have a natural buoyancy for them to float while capsized. | While it is a fact that catamaran are as stable standing upward as they are while capsized, advanced and more reliable forecasts should and in fact do limit there occurrences. But there is a cruiser forum titled “How many cats have flipped ?“, and the funnier post is “once per involved catamaran“. Another safety point to consider, in fact a way more common one, is crew safety on regular or heavy condition boat handling. While not precisely as “stable” as usually advertised, moving around a catamaran is considered to be safer than on the deck of a 20° heeled monohull. |

| Comfort | That’s where catamarans usually build a consensus. Larger living areas, both inside and outside, same-level galley (or chart table) to cockpit, 360° visibility while sitting on anchor, large protected outside space for foul weather watch … that’s hard to beat for a monohull below a very respectable size. | Some would argue, though, that both hulls aren’t exactly on the same level. In fact, not only do you have one more stair to deal with in a catamaran vs. a monohull, but they make it hard to communicate from one hull to the other in case of emergency. Of course, these would be grumpy sailors, who never experienced the little siesta in the trempolines. |

| Docking | Given their lower real estate surface, monohull are easier to maneuver in a cramped harbor, especially with the help of a bow thruster. And of course, the price will be cheaper, as catamarans are usually charged on a list price x1.5 to x.2 basis (not to speak of Capri, which charges based on the beam size). | With their twin engines, catamarans are amazingly maneuverable. That’s until you get a significant cross-wind precisely when trying to slip into that tight docking space. It all comes to windage of course, but we’ve missed a bow-thruster so many times over the last decade of docking a 45 feet cat Med-style, that this equipment will come high in the next boat priority list. |

| Preferred sailing area | Given the adequate preparation the boat hull design doesn’t seem to limit the targeted sailing area. | Best for intertropical zone, or mild climates. The truth is these latitudes are likely to concentrate the bulk of the global catamaran fleet, and you don’t see many above 45°N. |

We can’t dodge the fact that higher righting moment makes catamarans more stable than their comparable keeled monohull. Even while flipped over, and that’s the key point.

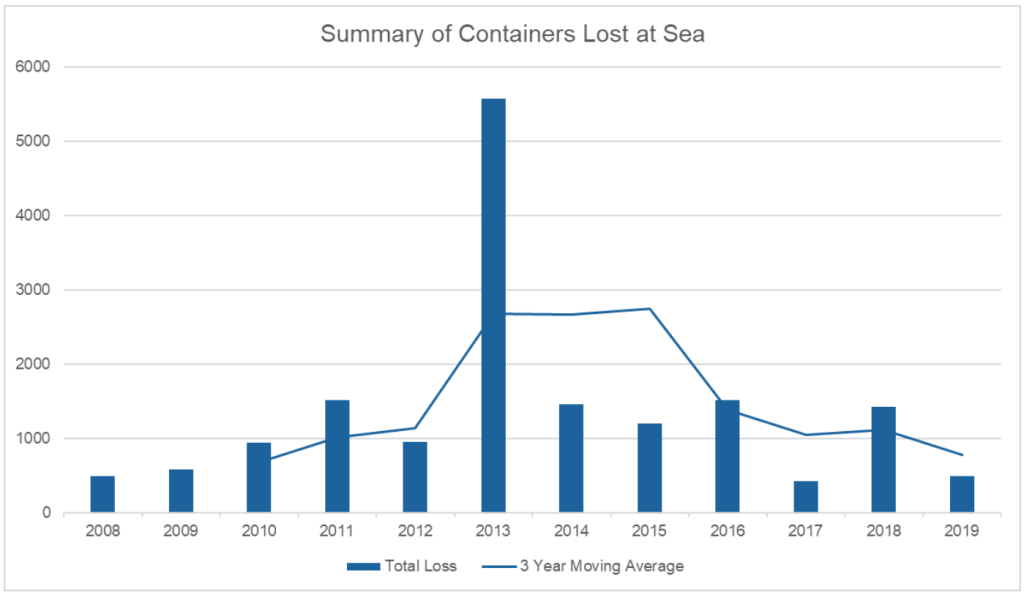

Given the fleet out there, this sort of accident seems so rare there aren’t any public statistics about it. Reading through some accounts of these, it’s hard to differentiate extreme and rare weather conditions – in which case a catamaran and a monohull are likely to experience the same fate – skipper unable to slow down a heavy cruising catamaran in big seas, and burying the bow in the forward wave, tripping the thing over, and last, some account of more sporty catamaran with daggerboard down, tripped over laterally by a really big wave. Other story will involve hitting a UFO, one hull making water before the actual capsizing, but the truth is, not all the details are available online with reliable sources for each of these stories.

The only rather rational information one can gather on this topic is the insured value percentage paid for insuring both designs. As per our broker’s feedback’ there aren’t any significant differences, which could lead one to think their accidental record doesn’t differ based on their design, including such definitive fatalities. But then again, there aren’t many cats sailing high latitude, and they’re more prone to hurricane accidents in the tropics.

As far as extreme conditions are concerned, modern weather forecasts combined with recent telecommunication progress reduce drastically the odds of being caugh in a nasty situation. More importantly, added speed coming with the second hull might help to move out of the way of the incoming gale with smaller notice – and that’s when weather forecasts are the most accurate.

At this stage, having extensively sailed a catamaran for a decade, together with some monohull experience as well, we wouldn’t want to add anything to the classic controversy between both designs. We’d rather try to takes notes on high latitude specifics, both challenges and benefits, coming with two hulls instead of just the one:

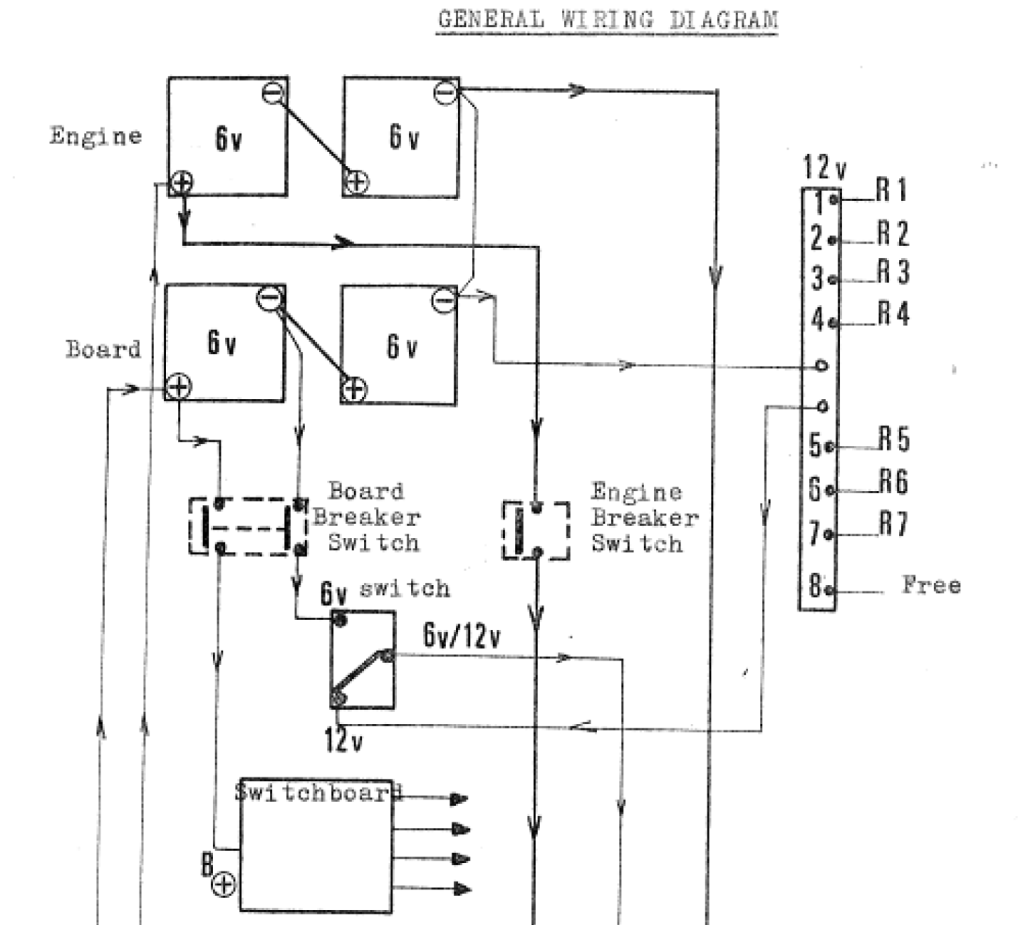

- Heating a larger volume on a cat, while at the same time more surfaces in need of thick isolation, or providing more condensation opportunities, this might be a challenge in very cold climate, inducing strain on fuel tankage and energy consumption. And at this stage, we never saw a gravity-fueled stove installed in a catamaran, neither have the Refleks guys we asked. On another hand, it is easier to fit two heating systems (redundancy of all key system principle), either with two identical hydronic system in each engine compartment, either with an hydronic system coupled with a connected fuel stove, should this be possible.

- Packed ice: one can see how ice may get jammed between hulls, while a monohull could slowly cut its way ahead, so that looks like a condition to avoid, implying seasonal sailing, and thorough ice forecast attention. There are a few catamaran which have ventured into the NW Passage, or down to Antartica (see below), but it seems really like an exception. Then, let’s not forget that the fatal dangers of being trapped by moving ice pack are the same for any small sized boat, monohulls and catamaran alike, especially if not specifically designed for overwintering on ice.

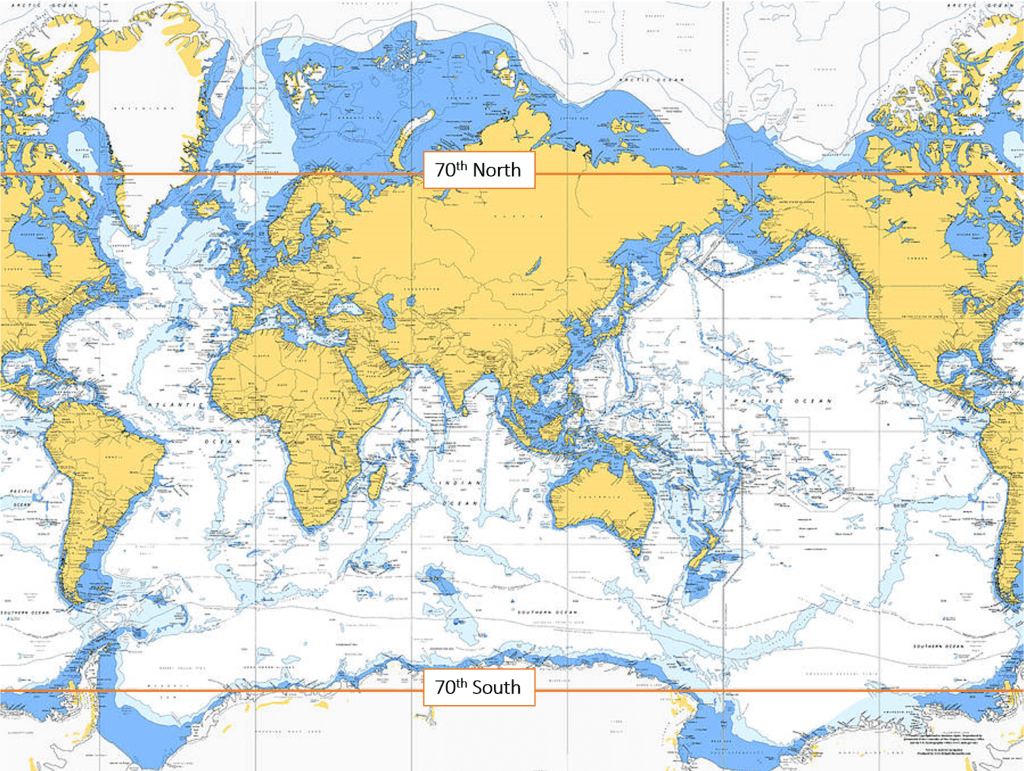

- Sailing zone: Speaking of ice, our plan is not to overwinter in these high latitudes. A very specific boat design is required for this. But should the opportunity present itself, we could consider sailing in areas with up to 2 or 3/10th of ice concentration, which can be encountered even in summer time. So South Svalbard why not, North East of it unlikely. This is at this stage the clearest limitation to 70th Parallel. Maybe should it be named 60th Parallel after all (name was taken).

- Fuel efficiency: that’s not supposed to come as a significant criteria when speaking of a sailing boat. Unless speaking of in-season (meaning summer) high latitude sailing, when wind will be light, at best. In case motor-sailing is required, catamaran are reputed for being more fuel-efficient than monohull on a windless sea, due to their lower wetted surface. In fact, running on one engine at the time can be quite a fuel-saver, when fuel autonomy is critical. In these conditions, we would plan for an average 0.8 l/nm.

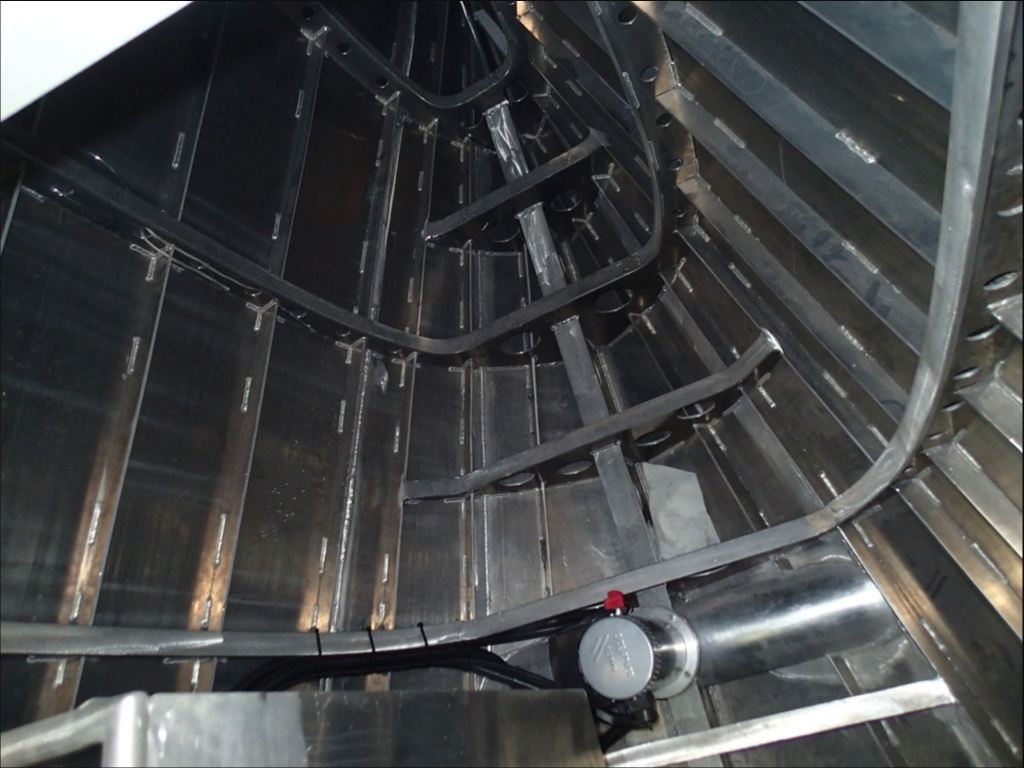

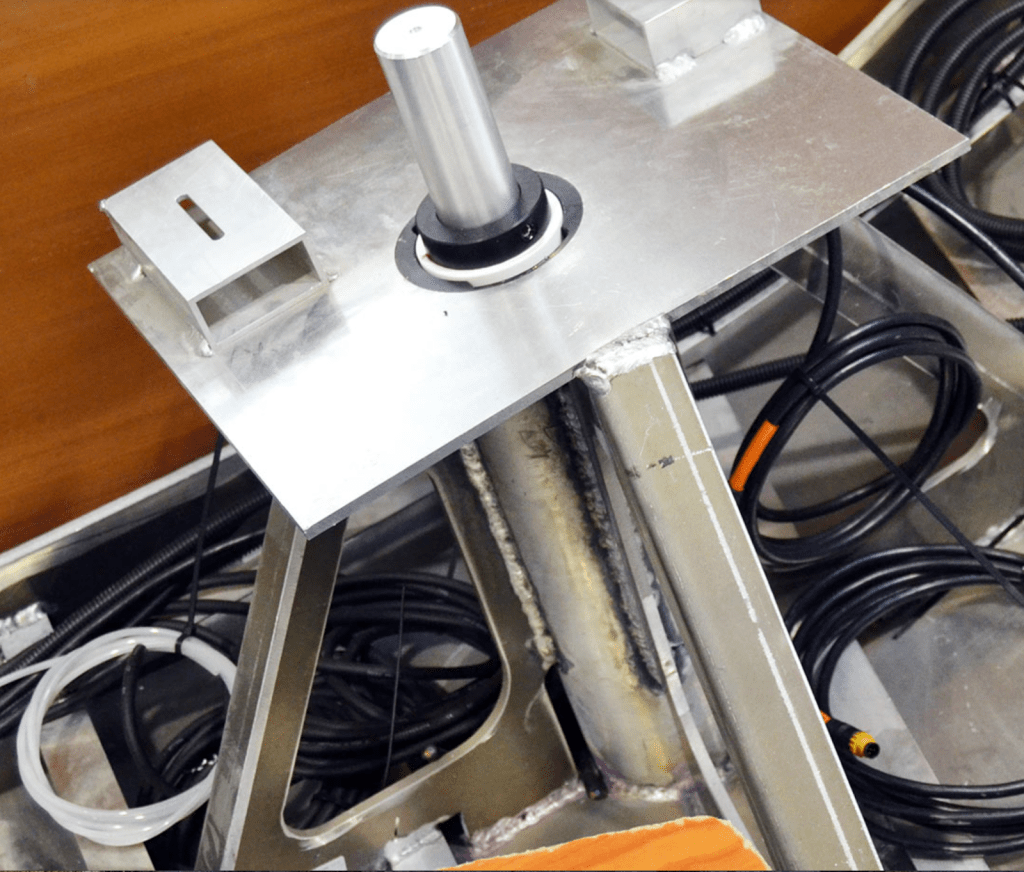

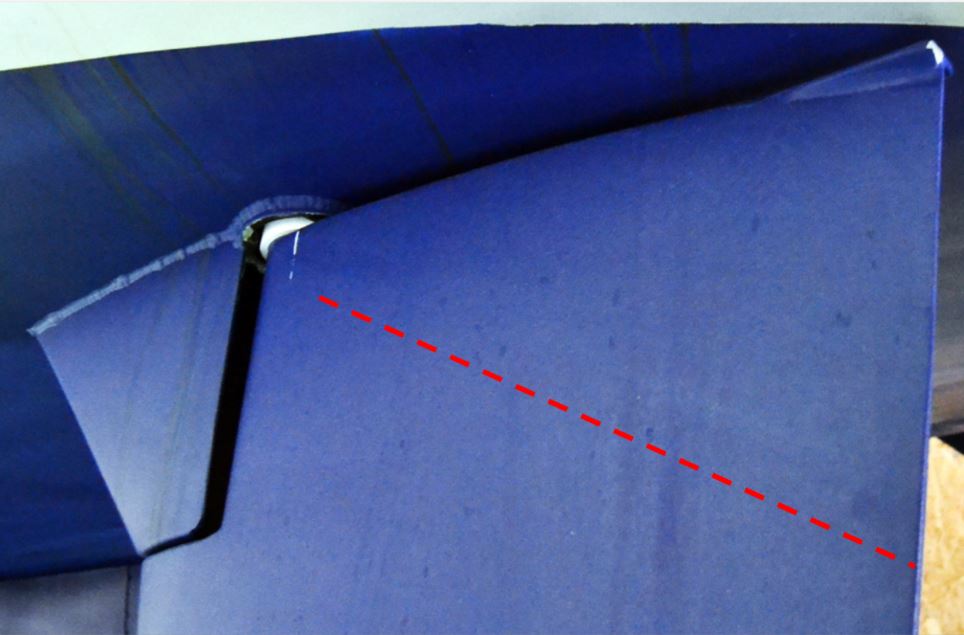

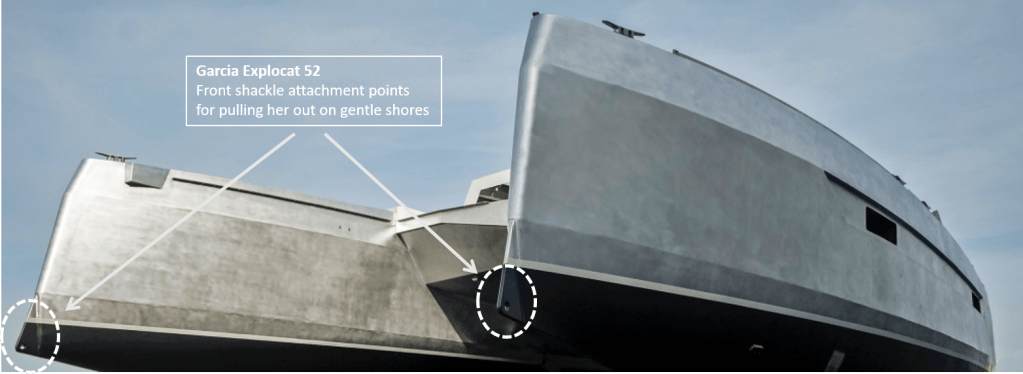

- Hauling out: the consensus is that facilities to haul-out an 20t catamaran with an 8m+ beam are quite scarce in high latitudes. On another hand, it’s easier for a cat to beach over a tidal swing, as these increase with latitude. The Garcia Explocat 52 has a smart hull design feature, allowing to attach two shackles and tractor her out of the water on any rolling logs, provided it is a gentle slope shore.

- Sailing speed: assuming a catamaran makes faster runs than its equivalent monohull, which is quite controversial (see above), speed would be an advantage, as weather windows are usually narrow in high latitudes.

- Capsizing: it happens. It can happen. How rare it may be, the consequences are life-threatening. The size of the catamaran and its weight distribution would matter tremendously. A 50+ feet catamaran with light rigging and centered weight, would be way more stable than the average 40-45 feet with both of its hull-peaks filled with high latitude-related stuff. In the potential choice of a Catamaran, these factors would be deal breaker criterias.

- Comfort: when on a long range sailing journey, the fact is we spend most of our time on anchor, or docked to this nice remote little public quay. Larger living quarters giving an all-around view is a benefit that’s hard to give up. Large rain-protected cockpit is priceless in any latitude. And above a certain size, say 50 feet, even the most performance-oriented catamaran is fitted with very comfortable cabins – not to speak of the huge so-called owner-cabin, in fact one whole hull with house-like amenities.

- Key system redundancy: considering the engine as one of the first key systems, especially for high latitude in-season sailing (in fact mainly motor-sailing), having two on a catamaran is one huge advantage over monohull design. With the one running engine comes not only mobility, but as well electricity, heating and hot water.

- Storage: that’s a two-sided argument. Catamarans have indeed larger storage space than most equivalent monohull – so, this is good for high latitude sailing plans. But their performance can drop drastically if overweigh, or if the weight distribution is less than well centered – beware of filling up the peaks with heavy stuff.

Not many of them, but there are some significant high latitude catamaran exemples which proves that at least some skippers have done it:

- ‘Arctic princess”, a Lagoon 450F sailing out of Tromso (2019)

- Leopart 39 delivery, sailing the southern ocean (and other such videos on Youtube)

- ‘Angelique II’, Outremer 55, sailing Antartica (2016)

- ‘Libellule’, Fontaine Pageot Salina 48 in the NW passage and Antartica (2013-2017)

- ‘Rum doxy’, 46′ Custom Catamaran both S. & N. high latitude sailing

- PataGao, an Atlantic 57 sailing Patagonia (2012)

- ‘Double Magic’, a Catana 431 visiting Antarticta

- ‘Wildfilfe’, a Catana 47 visiting Patagonia

- Elcie, a 62ft aluminium catamaran (DeVilliers design, built in New Zealand)

- (…)

The catamaran market is undeniably the fastest growing segment of the pleasure boat sector.

BusinessWire study (2019)

Many factors are influencing the catamaran market growth, the booming size of its charter segment not being the least, but this is irrelevant for us. Given that this trend is still young, it will surely increase the likelihood of seeing them in higher latitudes than their classic present turfs. On top of some isolated one-off initiatives, it’s significant that highly reputable aluminium boat yards, such as the French Garcia and Alubat, add an aluminium catamaran model to their range. One can dream of seeing Netherland’s KM Yachbuilders, another all-roads reference, adding one as well – after all they launched the Bestevaer 53 en 2020, a motor yacht.

here the aluminium Yapluka 47, launched in 2001, obviously well ahead of their time.

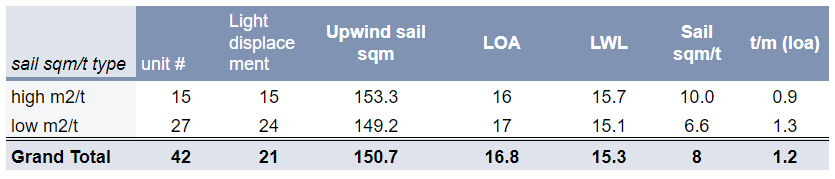

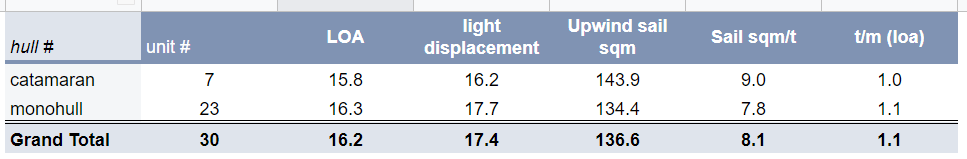

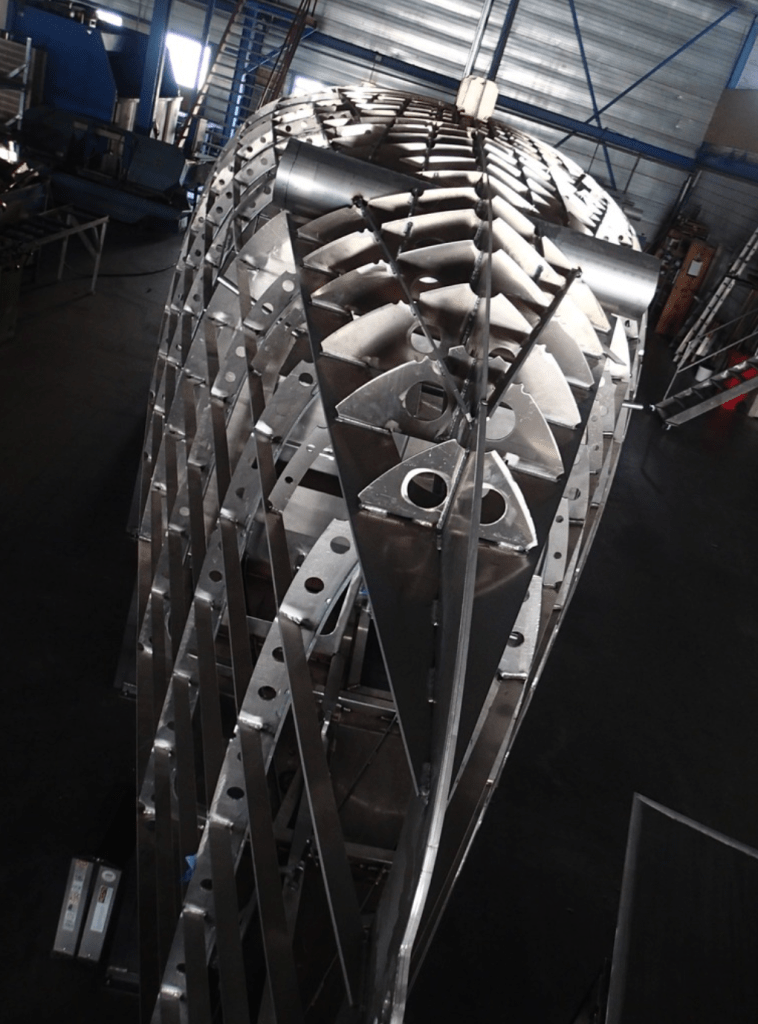

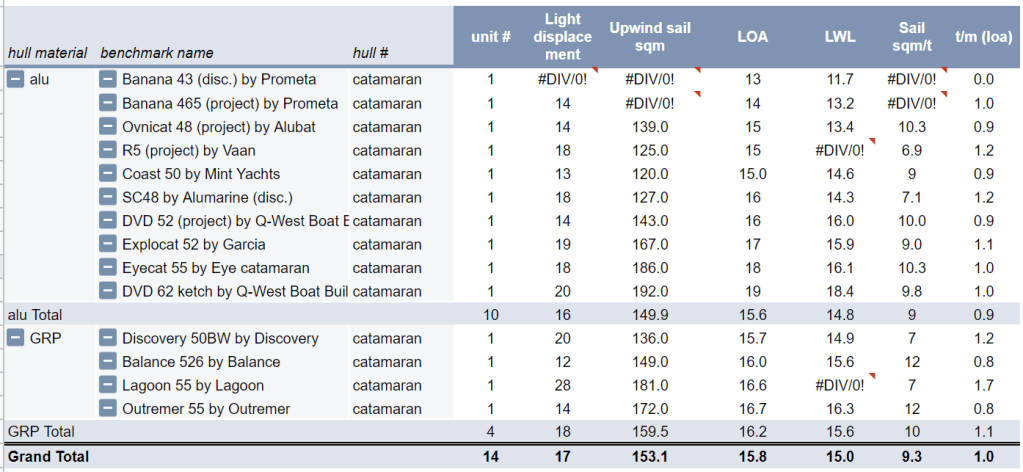

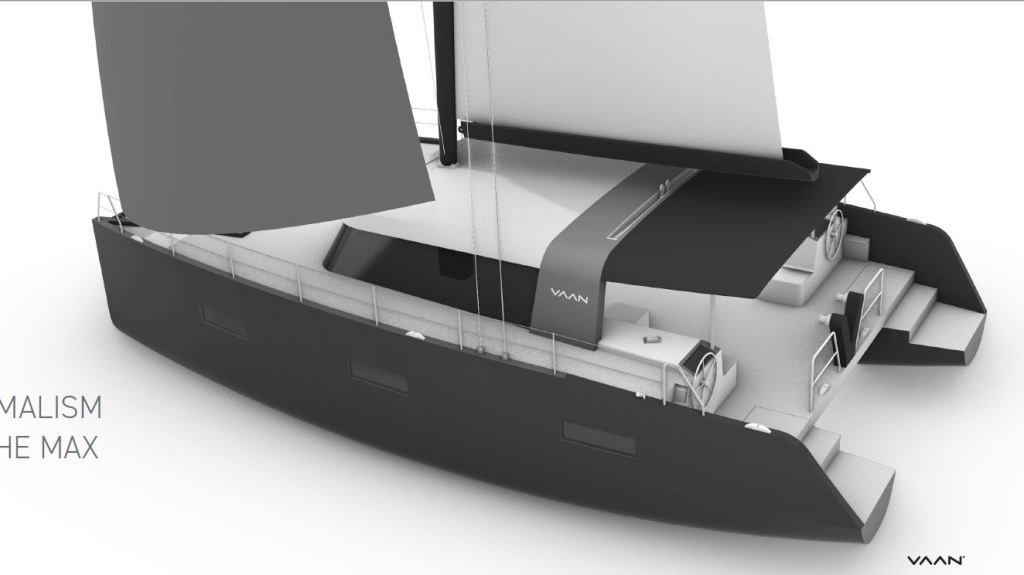

That’s the point, we only focus on the aluminium model, putting aside the high latitude preparation which is always possible for a composite model. So here comes the very limited list of aluminium catamaran we could set our hand on, with some current composite counterpart for benchmarking purpose:

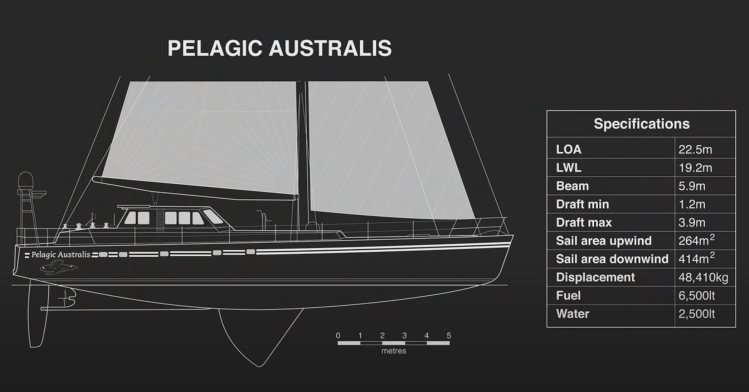

In this respect, the French boat yard Garcia seems to have the lead in this industry initiative. While Alubat only provides plans and designs for its Ovnicat 48 not only have Garcia pioneered this trend with its SC48 (to be fair, an Alumarine initiative, before being integrated to Garcia), launched in 2013, but it did it again with the launch of its Explocat 52 in 2020, despite the lower-than-expected success of the former. Seeing them side-by-side, one can guess one single architect has been behind both projects, and this would be Pierre Delion.

Other aluminium industrial projects exist, such as Prometa’s Banana 465 (heir to the ‘Banana Split’, famously skipped around the world by french singer Antoine), the Ovnicat 48, the New Zealand DVD 52, based on the first DVD 62 experience, or some one-off construction, like the Mint Yard Coast 50, or the Eyecat 55, but they are falling behind Garcia’s.

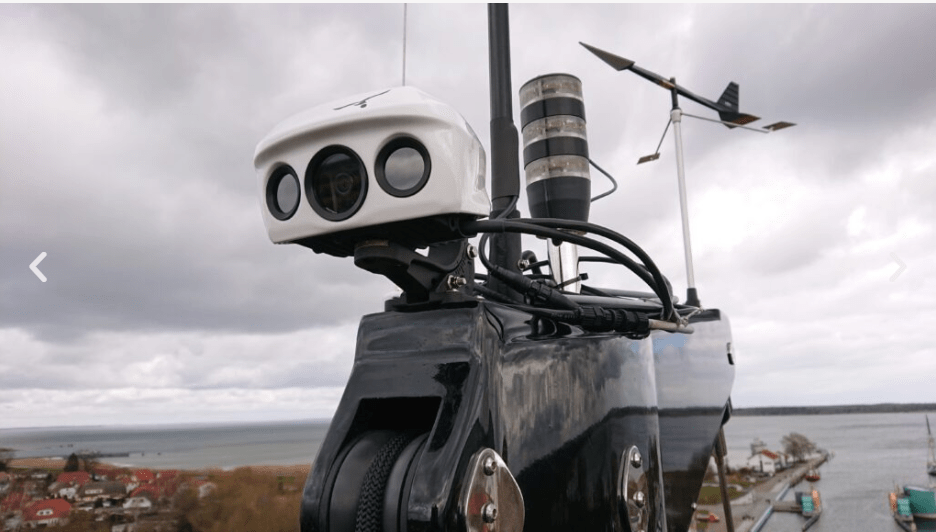

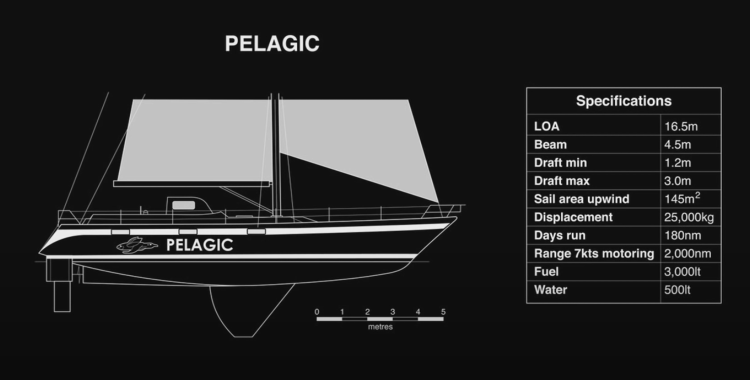

There are now two Explocat 52 units in the water and over 10 additional orders (Nov.23 edit : 5 in the water, including our “Anamor”, launched in Aug.23, and over 15 in total), with a backlog exceeding 3 years. Considering all the added benefits of fitting into twin hulls the rich experience gained out of their successful Exploration monohull range, this head start could last for a while.

Having completely missed the SC48 at the time of its launch, we were quite amazed to scroll down the Explocat 52 initial brochures and specs.

So that’s how we got to know Garcia better.