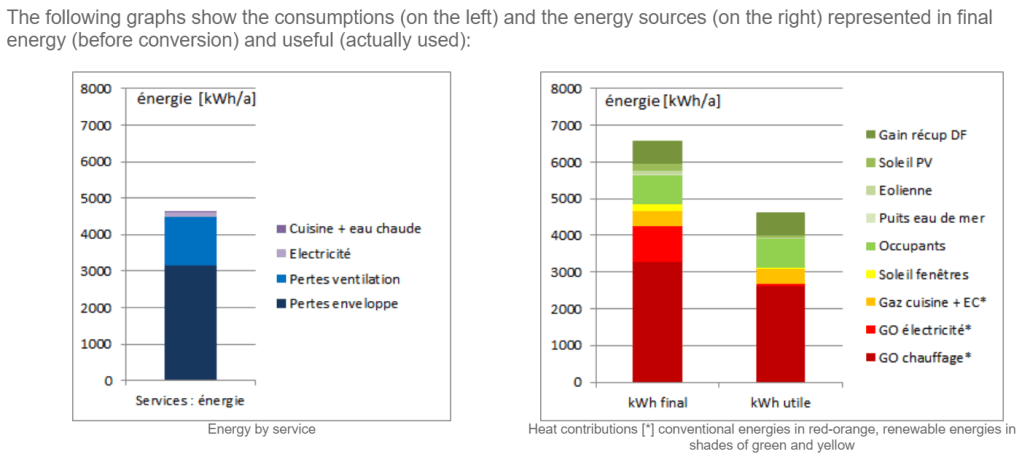

Nanuq is a 60 feet Grand Integral launched in 2014 and designed to minimize environmental impact while accommodating a crew of up to 12 in high latitudes, including during winter. Built with the same insulation standards as a passive house, one of its first scientific projects was to prove that its crew could live through an Arctic winter in an energy self-sufficient way (meaning no use of non-renewable energy). Even while making some extreme energy management decision which wouldn’t happen on a more casual cruiser, this initial scientific project proved in an extensive way that energy management on a boat was primarily a matter of insulation (66% of the energy consumed) and ventilation (28%), to be compared with the other consumptions (Electricity 4%, kitchen, water and hot water 1.5%, laundry 1.5%).

Insulation is one of the many topics which high latitude capable boats will differ from with the average mild climate cruisers. Nobody goes to a boat show asking “I wonder what type of insulation they use”. Its goal is twofold: (i) Prevent condensation and (ii) Optimize heating needs

Preventing condensation

Condensation will happen any time a warmer air will enter in contact with a cold surface, especially one with high thermal conductivity such as aluminium or glass. It defines the transformation of water vapor present in the air into liquid water on its surface. While we casually encounter condensation in our daily life, in a boat this phenomenon is not welcomed at all.

Everyday condensation

– Having a cold soda on a hot day, the can “sweats.” Water molecules in the air as a vapor hit the colder surface of the can and turn into liquid water.

Softschools

– Dew forms in the morning on leaves and grass because the warmer air deposits water molecules on the cool leaves.

– The mirror in the bathroom during a shower becomes foggy because warmer water vapor in the air hits the cooler surface of the mirror.

So isolation is essential, not only to optimize energy déperdition and heat production, but also to fight condensation. In this case, its goal is to keep the living areas’ heat away from any thermal bridge surfaces, such as hull and windows surfaces, and their framing as well, depending on their conception.

An addition to condensation coming from the external surface, humidity level in the boat is related to simply living aboard:

- Humans perspire and exhale 40 to 90 g/h of H2O vapor depending on their metabolism and activity level. A crew of 4 would produce 4 to 6 l/day of water vapor.

- Drying clothes indoors: 1.5 l/d

- Gaz cooking: 3 l/d (Propane or Methane + x.02 = CO2 + y.H20)

- Electricity: 2 l/d

- Dishwashing: 0.5 l/d

- Washing clothes: 0.5 l/d

Propane: C3H8 (molar mass: 3*12+8*1 = 44g/mole)

water: H2O (molar mass: 2*1+16 = 18g/mole)

full burn formula: C3H8 + 5 O2 -> 3 CO2 + 4 H2O

So burning 1 mole of propane (44g) produces 4 moles of water (4*18g=72g).Butane: C4H10 (molar mass: 4*12+10*1 = 58g/mole)

Anonymous sailor who didn’t sleep over chemistry classes

full burn formula: 2 C4H10 + 13 O2 -> 8 CO2 + 10 H2O

so burning 1 mole of butane (58g) produces five moles of water (5*18g=90g).

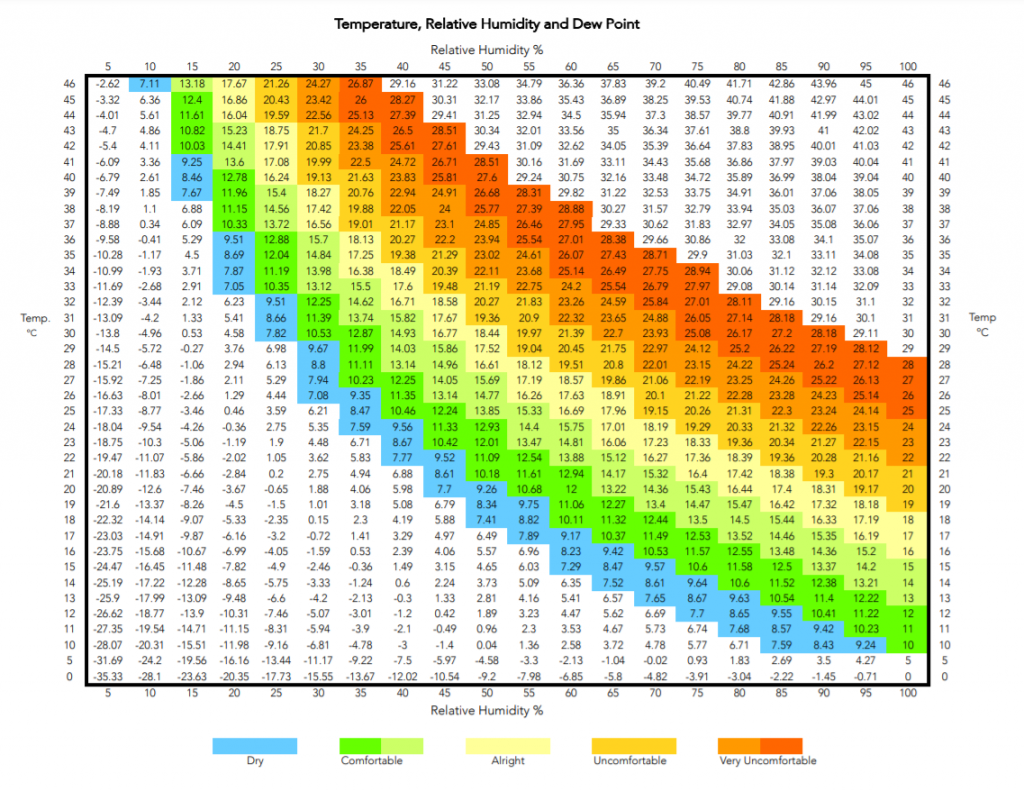

The air’s capacity to hold onto that humidity depends on temperature. Relative Humidity (RH) tells us how much water vapor is in the air, compared to how much it could hold at that temperature, shown as a percentage.

The Dew Point (DP) is the temperature the air needs to drop to in order to reach 100% RH. At this point the air is fully saturated with water, condensation forms, and that’s when mold/mildew forms and life becomes uncomfortable.

Depending on the activities onboard, unless you want water dripping from all windows and other metal surfaces, the only way to deal with high humidity level is to ventilate the boat.

Easy said in mild climate, not at all convenient in high latitude freezing temperatures.

Ventilation

While critical on a wood hull, ventilation will be a necessity on any other hull material to deal with condensation and humidity levels, preventing mildew for instance.

This is a topic we’re still working on, but at this stage, we expect both forced ventilation in the bilges and passive ventilation (why aren’t there any dorade-type ventilation systems on catamarans?) in the living areas.

Given the importance of humidity coming out of the galley, a forced-air extract system might be a good idea for high latitude sailing, when the boat is tightly closed.

We plan on implementing bilge forced ventilation on both hulls, based on brushless fan technology, which will induce lower energy consumption.

Badasse’ Brushless Model 4 Marine Fan: 190CFM, IP67 Waterproof? 2.5 Amps 8-16v. claims 40% less current than brushed equivalents.

Hull insulation

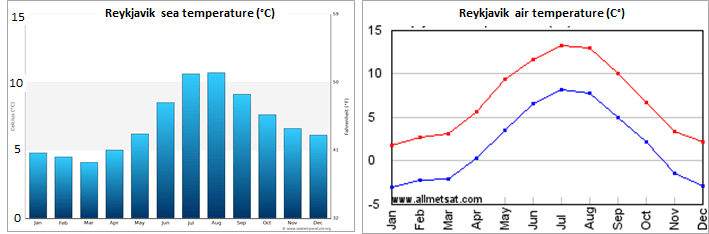

Unless you plan for ice over-wintering, with a specific related boat conception, the sea would be considered as an insulation agent against external temperature. In Reykjavik, for instance, sea temperature wouldn’t go below 4°C, even during the cold winter months, when average temperature would be below 0°C (oct-apr). This is slightly countered by the fact that water has a much higher thermal conductivity than air.

This is one reason why we plan to isolate the hull from water-line up and including under-deck. Another one is related to the fact that should anything happen to the hull below the water-line, it’ll be easier to diagnose and deal with if not covered by a thick insulation layer. Lastly, in tropical areas, we’d probably be happy to get some inside cooling out of the sea temperature.

Regarding the hull, insulation will usually be done with foam or fiber, and the thickness would depend on the temperature difference expected between the inside and the outside of the boat. This needs to be done very thoroughly, especially on any “thermal bridge” material, such as window metal framings.

Warm will find its way behind the insulation, and this is when condensation will happen, particularly on metal of glass surfaces. And over time mold is likely to form, in places where it’ll be difficult to deal with.

The most commun isolation techniques are spray foam and closed-cell, elastomeric or extruded polystyrene, foam.

- Spray foam

- On a steel hull, when condensation can lead to hull oxidation, the issue is not only about comfort. These hulls would usually be isolated with spray-on Polurethane foam. This product has different commercial names (thermal insulation foam, insulation foam, spray PU Foam, 2 component spray PU Foam, heat and acoustic spray insulation foam), and while its application will bond an insulation coating to all surfaces, it don’t seem adequate when in need of thicker insulation due to extreme outside temperatures.

- Closed-cell elastomeric foam, such as Armaflex

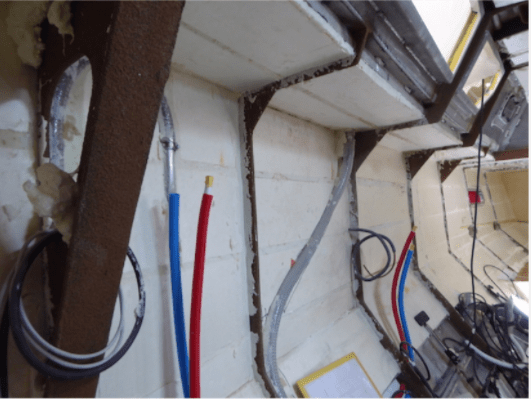

- The tricky part with Armaflex is to ensure its perfect bounding with all surfaces, including parts where metal welding makes it difficult to ajust foam shapes (“covering every nook and cranny”, as KM Yachtbuilders would say it).

- And of course, expressing concerns about long term bounding of the adhesive.

AF/ArmaFlex is the professional flexible insulation for reliable continuous condensation control. Its unique microcell structure makes the product easy to install. The optimal combination of a very low thermal conductivity and extremely high resistance to water vapour transmission prevents long-term energy losses and water vapour ingress and reduces the risk of under insulation corrosion.

armacell.com

- Closed-cell extruded polystyrene foam, such as Styrofoam

Deck insulation

As we have insulated all the inside from water-level up to the deck, of course under deck surfaces and all superstructures have been covered with the same insulation foam material.

Additionally to this under deck insulation, while most high latitude sailing boats will keep their bare deck aluminium surface just covered with non-slip paint, we’re planning to add a faux-teak surface. At this stage, this is one of these compromises which come for a boat which will not be 100% high latitude. We’re thinking about how a tropical sun shining on an aluminium surface is likely to transform it into a giant radiator, not to speak of the barefoot walking on it.

We can think of only two drawbacks:

- There is always the risk of corrosion beneath the covering. The probability is pretty low, as water has to penetrate under the material, but it would be difficult to detect until a very advanced stage is reached, and the consequences would be dreadful.

- And secondly, it adds some weight on the boat.

But we think the benefits outmatch these, especially while coming back to high latitude and/or winter sailing, where this additional layer would increase furthermore the deck thermal insulation, provided we pick the right material.

Flexiteek 2G on an X40 deck

Permateek on a 60 footer

Marinedeck 2000

| Flexiteek | Permateek | Marinedeck 2000 | |

| Material | PVC with REACH compliant phthalate-free plasticizer, fully recyclable | Outdoor grade PVC | Cork granules with polyurethane. Cork a is natural product with high insulation grade. |

| Weight (kg/m2) | 4.5 (5mm) | 5.4 (5mm) | 2.4 (8mm) |

Between a PVC-based material, even of the recycle type, and a natural cork-based one, there is little to hesitate for, especially if you consider its weight. So Marinedeck 2000 will be. It might add 80-100 kg to the global boat weight, but to our eyes, the benefits outmatch this, especially if it makes it unnecessary to add an extra foam insulation layer below deck. And by the way, we love the natural look and feel of it.

Floor insulation

Given the thermal characteristics of aluminium, the area under the cabin floorings will eventually get to a temperature nearing the one of the sea. Although this will never be as extreme as the air temperature, the floor insulation equally needs some insulation attention.

Since the temperature to deal with isn’t as extreme, and as well to save weight, the floor isn’t necessarily isolated underneath. However it has an insulating foam core, and while sailing cold areas, we plan on setting a wool carpet in all the cabin areas, and maybe around the table in the living space.

Windows insulation

Coming back to Nanuq’s takeaways, the biggest heat leaks are going to be windows, hatches and door openings.

Opening hatches and portholes are prone to condensation because of their high thermal conductivity aluminum framing. The only way to achieve a thermally broken profile is to assemble the inner and outer framings with some thermal insulation material in between (polyamide for instance).

- Large living area windows and doors

- Deck hatches

- Hull portholes

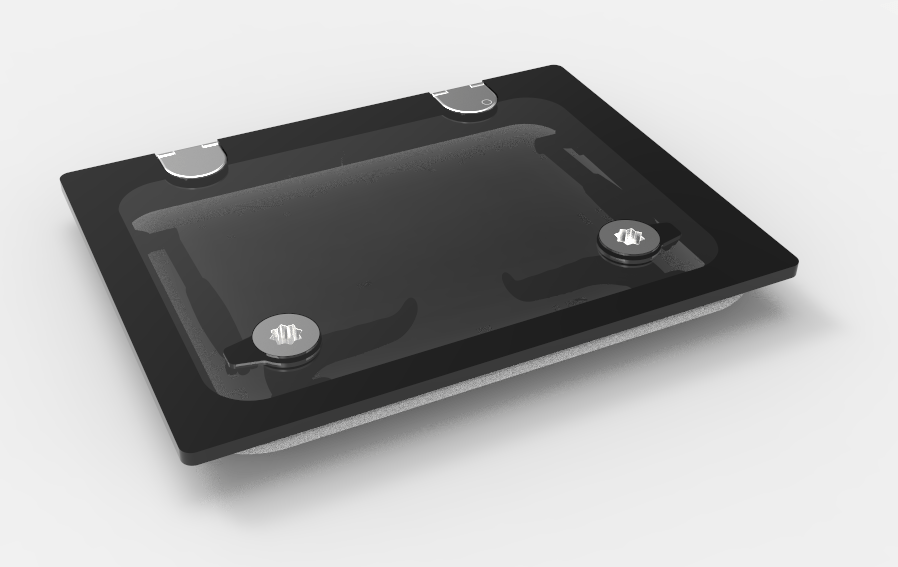

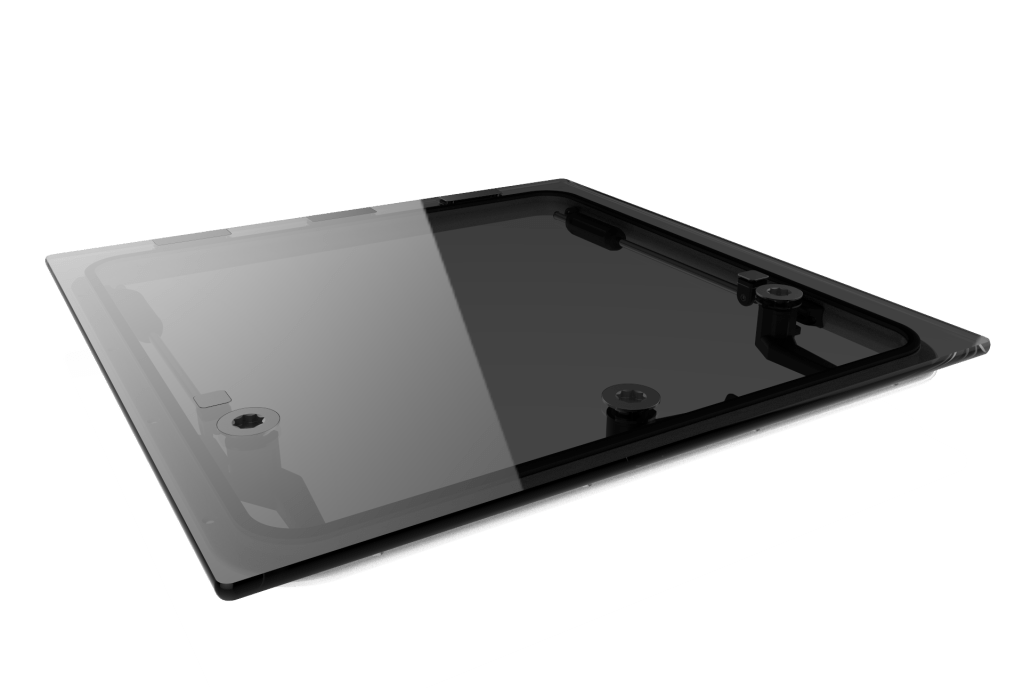

Goiot – 15mm acrylic, mounted on stainless hinges

Lewmar – Flush Hatch 3G 10mm acrylic

Lewmar – Flush 3G schematics

Condensation will eventually appear on the window surface, and especially on their aluminium framing. There are horror stories of so much water dripping on bunks beneath that it would make them unusable for sleeping — and try to think of the time required to dry them. Basically, you want no aluminium hatch frames exposed to the moist warm interior air, meaning either a specific framing design, or a double insulation.

On top of carefully selecting the hatches and porthole for thickness and framing structure, the only way to prevent it is to create a double layer of insulation, either inside or outside.

And this is where we’re looking for double glazing for all the large living-area windows and doors. We know this is a big weight investment, adding circa 400 kg to the total, but we can’t see any definitive way to deal with the condensation induced by such large surfaces.

We read about this Arctic expedition sailor, who planned for his next boat to run heated tubes under his living area windows to prevent condensation, but given our layout, we don’t think it’s realistic with heated tubes. Following-up on the same line of thoughts, maybe a heat-exchanger coupled with thin slits just beneath them could deal with the living-area very large windows issue.

- Living area windows (way too large, but this is part of the design) are 10-12mm tempered glass.

- The front deck hatch is 15mm acrylic, but we’d rather 15mm tempered glass.

- For the large living area window, we’d like a thin (say 3-4mm) aluminium storm cover which could be fitted when confronted with a hurricane.

So at the moment, we’re weighing options between double glazed and way too heavy windows and the very thick tempered glass one (circa 10mm) with decent thermal insulation, in which case it would be coupled with air exchanger at their bottom.

Appendix

In no way do we have the scientific background allowing for any deeper comment on Young, Hugh D., University Physics, 7th Ed. Table 15-5 extract here.

The only significant consideration we’d like to share is its highlighting that aluminum is one of the least insulating materials, while Polyurethane is the best. In between, it would validate our choice for a cork-based, over hull, additional insulation layer.