Being a rookie has its advantages. It allows you to search for inspiration from role models you get to pick, and the unlimited access to online information streamlines drastically the process. And beyond the smartass answer (“Its crew is what makes a high latitude boat”), we’ll try to understand the specifics of such a boat, structure, preparation and equipment. Shown here, Morning Haze, an aluminium Bestevaer 55ST, is the typical high latitudes yachts, as an illustration in an 2019 Yachtworld article (©Benedict Gross).

A few names will quickly come up on the tip of your fingers:

- Skip Novak, the leader behind Pelagic Expeditions, specialized in Patagonia and Antarctica expeditions who generously shared his experience online.

- Gerard Dijkstra, the naval architect and sailor who envisioned the Bestevaer yacht line, working with KM Yachtbuilders in The Netherlands.

- Philippe Carlier, a man of so many adventures it’s hard to recount them, so we’ll focus on his high latitude tropism, illustrated by the launch of Qilak, his latest boat.

- Jean-François Delvoye, who not only imagined the Boreal concept during his 6 family years trip, but would launch in 2005 the very successful yard which would make them available to other sailors.

- Jimmy Cornell, author of World cruising routes, who sailed the NW Passage with s/v Aventura IV, his Garcia Exploration 45.

And behind these very preeminent figures come the numerous anonymous contributors willing to share their experiences and visions.

We started to read anything and everything related to high latitude. And of course we watched Skip Novak’s video on sailing techniques in the Horn weather, along with others from anonymous sailors. It all revealed a fascinating sailing world, existing beyond the ones we get in milder latitudes.

There are the sudden katabatic winds, not unlike the treacherous ones blowing over Greece or Croatia in summer. There are the big waves, big enough for the thought of being rolled-over to overcome any other consideration. There is the cold, meaning a whole new boat organization, and clothing as well. And of course, there is the ice, with it’s own forecast and a whole new set of sailing rules and constraints.

All of these get your heart to beat faster, but your mind quickly catches-up to define three top-level criteria what would define a high latitude compatible sailing boat.

- Rugged construction, to withstand hitting ice and the odd rock in uncharted waters

- Autonomy, meaning abundant storage, tankage and space for redundant systems and their spare parts

- Seaworthiness, while dealing, or dodging, with extreme weather and sea states, which is more common and harder to avoid in high latitudes

“They are tough, they are comfortable or they are fast,

you can only pick two of the three”

It’s easy to see how these requirements can oppose themselves. Many specialized high latitude boats are built like tanks, with strength contradicting weight requirements for any decent seaworthiness. But then, high in the North, or along the Antarctic peninsula, they would usually motor more than they sail, requiring huge fuel tanks.

This is not new. Any boat owner had to walk himself toward the compromise he felt best for his specific sailing program and lifestyle, even in sailing areas with little imperatives, like for instance being the fastest at sea, but with all amenities on anchorage.

The only difference that comes to mind with high latitude sailing is that the required fittings dont seem to be negotiable in these areas, and so any compromise would have to be related to less demanding sailing zones.

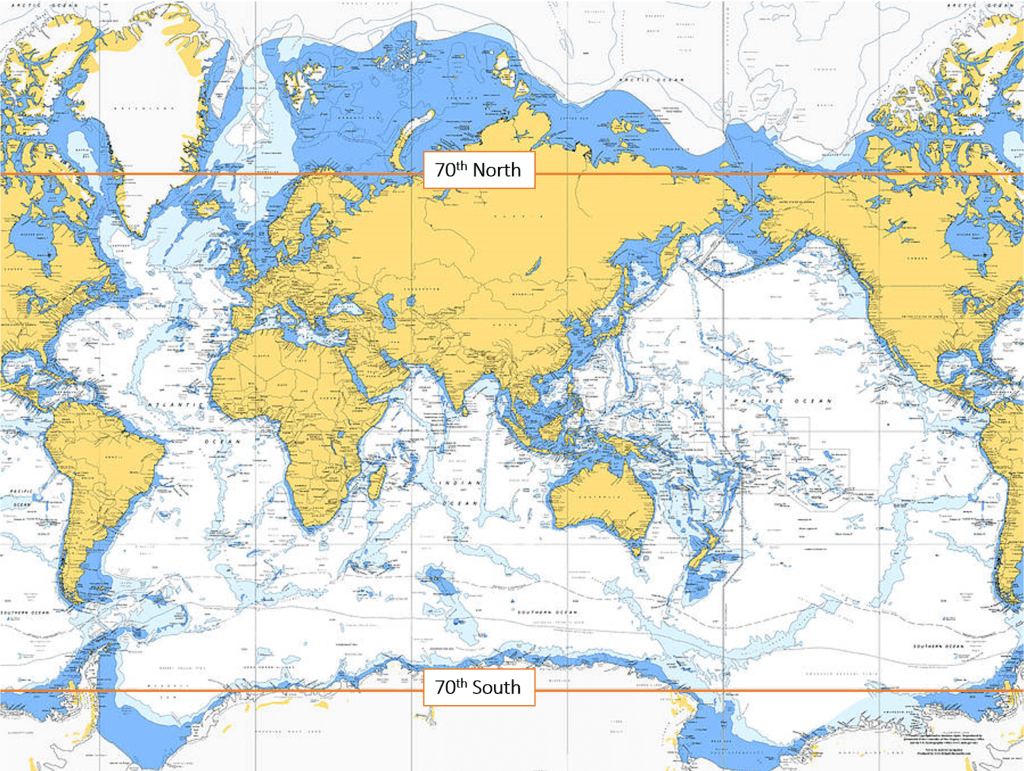

As far as High Latitude is concerned N and S. aren’t exactly equivalent. While Iceland and Lofoten are places where most cold-isolated boats could sail to, Antarctica, or even Patagonia is another matter. Very few boats are strong enough and specifically designed to sustain being held in ice, or to overwinter on ice. In any case, this is not something we’re looking for.

What would Skip Novak say ?

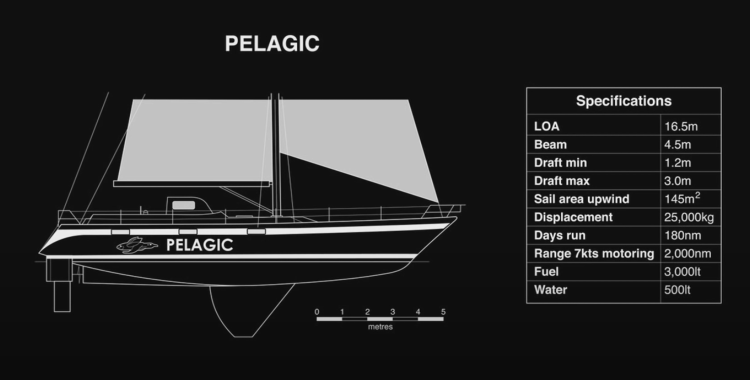

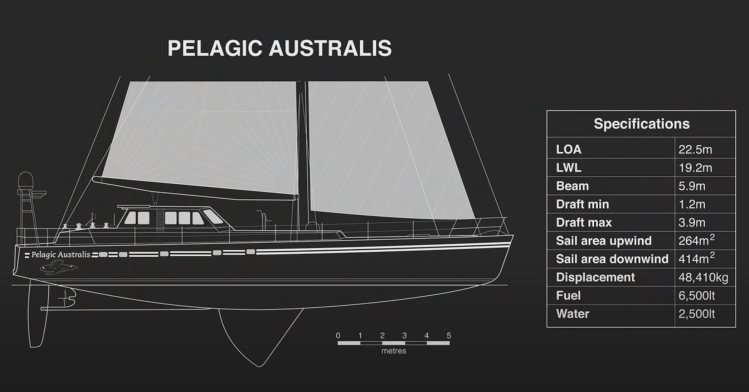

Searching for experience and inspiration, it was hard not to start the journey with the video tour of Pelagic and Pelagic Australis performed by Skip Novak on YouTube.

Let’s take note of some keyword along Skip’s tour of the boats:

- Robustness and simplicity

- Ability to beach

- Refleks stove, defined as the life of the boat, fed by gravity day tank. In Pelagic Australis, used to heat all the radiators throughout the boat.

- Self sufficiency, ability to repair anything

- Big workshop and storage area in the peak of Pelagic

- Pilot house, great for being out of the weather while still watching around

- Diving compressor on both boats

- Lifting keel

- Four reels of 120m polypropylene mooring line on deck of Pelagic, 150m for Pelagic Australis

- All safety equipment at the ready near boat entrance

- Watertight doors (Pelagic Australis)

- Two inflatable dinghy and two outboard engines

- A winch at the foot of the mast able to cope with windlass failure (Pelagic Australis)

- Clean deck while crossing the Drake

While Pelagic is built with steel, Pelagic Australis is an Aluminium boat. Built by KM and delivered in spring 2021, the 77 feet Aluminium schooner Vinson of Antarctica is the latest addition to Skip’s high latitude fleet.

There are flying fish, but these aren’t the majority of the specie

So what kind of boat construction should be considered? Material coming first, the rugged criteria seemed to rule out composite construction (generic for Epoxy/Kevlar/Carbon material), although it’s not at all that simple.

| Aluminum | Composite | |

| Construction | Perfect for one-off projects, as there is no need for a mold. Alloy is easier for the owner (or a surveyor) to check quality insurance – so particularly great for boat yard with a short track record | Cheaper and quicker mold-based construction. Alloy can be designed to be strong and stiff, but so equally can glass structures, especially when reinforced with Kevlar. |

| Impact resistance | More likely to deform | More likely to crack |

| Ice abrasion | Unless sailing at night, or lowering steering watch, ice is more about bow & waterline abrasion than impact. The ice skim also will gouge aluminum (which is, in fact, softer than kevlar/epoxy) | Glass boats in high icing latitudes would often have stainless plates bent to protect their bow waterline areas from ice abrasion when breaking through thin (15-25mm) ice surface. |

| Corrosion | Alloy (inc. ‘marine grades’) has corrosion concerns both electrically and with stainless fastners. | This don’t exist with glass construction |

| Insulation | Alloy needs 75mm of foam) because of its high thermal conductivity … | … but the requirement for thick isolation is valid for any high latitude boat. |

| Rigidity | In rough seas Alloy boats will usually be more rigid than their glass counterparts … | … but this will greatly differ from one yard to the other. |

| Repair | They can both be repaired in remote places, … | … for an owner without welding skills and equipment, glass is easier. |

That being said, reading stories after stories of metal boats sailing into high latitudes – Aluminium for the most recent under 60 feet units, that’s the preferred hull material we decided to pick.